Fundamentals of Forest Resource Management Planning

Published: Apr 30, 2020 | Printable Version (PDF) |

Puskar Khanal and Thomas Straka

LGP 1047

Forest resource management planning is a process that usually produces a written management plan. Forests by their nature are long-term enterprises, and the forest owner’s expected outcomes, like the forest conditions many years into the future, require actions today and over time to ensure these outcomes occur. Forest resource management planning does not always involve management objectives that include timber directly, but most forest management objectives do involve active forest management and timber at least indirectly. For example, timber must be manipulated to achieve wildlife habitat objectives, to produce recreation opportunities, or to produce exceptional vistas. 1

Without proper planning, forest owners may find that future forest conditions do not meet their management objectives. Planning ensures sustainable management of forest and land resources. Planning can ensure profitability, if that is an objective, by timing the thinnings and final timber harvest to be financially optimal. It can ensure the development of wildlife habitat to encourage selected species and that the forest has desirable recreation potential. 2 Proper forest resource management planning can even minimize the income taxes paid at timber harvest or provide for a forest estate that spans generations. The silvicultural prescriptions of today will determine the forest of tomorrow, and without proper planning, that forest may not meet the owner’s goals and expectations. 3

Elements of a Forest Resource Management Plan

In the next section, links to two commonly used templates for a complete forest resource management plan on private forest lands are provided. Those templates are detailed, as are most management plans, but all forest resource management plans tend to follow an outline that contains the same basic elements. 4

Property description/location and history are usually a starting point. The property description and tract history give context to the management plan. This can save the planner time in terms of determining prior activities that might impact current silvicultural options. For example, in the Upstate of South Carolina, the fact that an area of the forest was once a cotton field might be relevant. Silvicultural activities attempted in the past could also be relevant. Any old or current maps or past management plans would prove valuable to the planner.

The forest owner’s management objectives are almost always at or near the top of the plan. They give the plan direction and indicate the wishes of the owner. Often the management plan contains both goals and objectives. Goals are broad and tend to be long-term (i.e., increased forest profitability or enhanced wildlife habitat). Objectives are more concrete and tend to be shorter-term than the goals and are expressed in quantifiable terms (i.e., 10% increase in timber revenue or wildlife habitat doubled). 4

The forest is usually broken into stands, and these are sometimes combined into blocks or management units. Maps will define the stand boundaries, and other maps may define other attributes like soil type. Each stand is first described, and then recommendations are made by the forester or other natural resource professionals. Sometimes this happens stand-by-stand, each stand is described, and then recommendations are made for it. Other times stands are first described, one by one, and then recommendations are made for each stand, one by one. Either way, descriptions precede recommendations. The description is commonly called the current stand conditions. Current stand conditions could include the specific history of past activities that occurred on the stand, forest type, site index, age, timber volume by products, wildlife habitat quality, or any number of measurable and qualitative attributes that are relevant to the management objectives. 5

Recommendations or prescriptions are made for each stand. Desired future stand conditions are specified in terms of meeting the forest owner’s objectives. A forest management regime that describes what activities will take place in the forest and when they occur will be developed. The management regime sometimes includes cash flows, so that the owner knows costs and revenues to expect over time. Typical forest management activities that will be included are timber harvests, stand regeneration, thinnings, timber stand improvement, prescribed burning, herbicide and/or fertilizer applications, wildlife habitat improvements, and measures to ensure water quality (best management practices). The essence of the management plan is that the set of activities and their timing should combine to meet the forest owner’s objectives. 6

The management plan should also consider forest natural resource enhancement and protection. To meet forest certification system requirements or to qualify for cost-share assistance, assurances that forest sustainability standards will be met must be included in the plan. Air, water, and soil protection must be established. Forest health issues should be addressed. Protection from wildfire should be part of the plan. Fish, wildlife, and biodiversity must be protected (specifically endangered or threatened plant and animal species). Protection of special sites and social considerations should be taken into account, and the impact of the plan on adjacent stands or neighboring properties is also a concern.

Most forest resource management plans contain a management activity schedule that outlines all forest and other management activities, and when they occur. Forest owners find this an invaluable way to track the timing of forest management activities. While they are hard to project, sometimes the forester includes the timing of the costs and revenues associated with the forest management activities.

Resources

There are two excellent sources for a guide and template to assist foresters and landowners in developing a comprehensive forest resource management plan that will meet most forest sustainability standards and qualify for most cost-share programs. Both meet national Forest Stewardship standards.

- A Guide for Foresters and other Natural Resource Professionals on using Managing Your Woodlands: A template for your plans for the future (USDA National Resources Conservation Service)

- Management Plan Template (American Tree Farm System)

Reasons for Planning

Why plan? What makes forest resource management planning necessary, and what are the rewards? Many forests have no plan in place and end up fine. Sometimes this is true, but sometimes naturally regenerated forests are not in good condition. The need for planning is fundamental to achieving forest management objectives. If you do not have a plan, you will rarely end up with the results you hope to achieve. It takes specific objectives to achieve specific outcomes, or else the results will be random. The following are the major reasons for planning:

- Identifies the opportunities, limitations, productive capacity, and incremental cost to utilize that capacity. It assists in the identification of problems in the forest and encourages the forest owner to consider addressing them.

- Requires the collection of data on the forest and the subsequent analysis of this data in terms of the forest owner’s stated goals and objectives, perhaps leading to adjustments to those objectives (via an analytical view of the forest).

- Allows for consideration of financial issues that motivate the forest owner, like the expected rate of return, taxes, and estate planning.

- Identifies the resources (labor and capital) necessary to carry out the forest owner’s objectives, and how needs might change over time.

- Allows for a long-term focus on forest management (beyond the current problems), identifying alternatives that could impact the forest well beyond the lifetime of the current owner.

- Provides evidence of forest stewardship. A forest resource management plan is tangible evidence that planning has taken place. Another natural resource professional can determine the level of planning and confirm that forest stewardship has taken place.

- Provides a framework for forest sustainability by defining projected forest outputs and determining whether these outputs are sustainable over time. For example, forest certification and federal and state cost-share programs require a forest resource management plan to document that sustainability exists.

- Allows the forest owner and planner to evaluate the trade-offs between goals by identifying the alternatives and resulting outputs that can be valued by the forest owner. The forest owner will be presented with any conflicting goals, and the planning process will allow the owner to resolve those conflicts.

- Allows for ensuring compliance with federal, state, and local environmental laws and regulations. The planning process should identify relevant laws and regulations and attest to compliance. If errors are made in terms of compliance, the plan will provide evidence of a good faith effort to comply.

- Allows for the efficient scheduling of forest activities. Regeneration, harvesting, and silvicultural activities occur simultaneously and continuously in many forests. Planning and scheduling are necessary for cost-effectiveness and can even identify equipment or labor shortfalls before they occur.

- Allows for forest outputs to be matched to expected markets. Planners should have some expectation of future timber and other markets and should be able to time forest outputs to take advantage of those markets.

- Allows for continuity as forest owners and foresters change over time. Prior forest owner objectives will identify where the plan was “taking the forest.” Forest resource management planning takes place over a continuous timeframe; management plans are dynamic, not stable, and can reflect management that exceeds the lifetime of any one forest owner. 7

Elements of the Planning Process

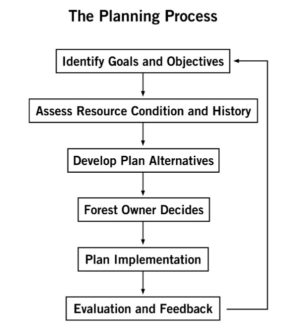

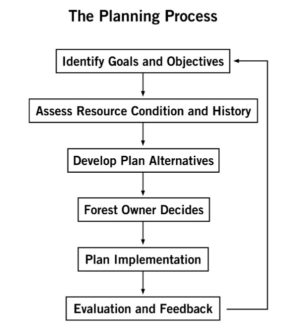

Forest resource management planning derives its value from setting direction by looking at both the short-term and long-term planning horizons and providing an analysis framework for achieving the forest owner’s goals and objectives. The planning process provides for adaption to changes and new information, with feedback being an important element. Many planning models are used in forestry, but the typical steps involved in the planning process are the following:

- Identification of the goals, objectives, and timeframe of the current and, perhaps, future forest owner(s). Goals are broadly focused, abstract, and are usually stated as general intentions. Examples of goals are to manage the forest for profitability, to increase aesthetics, to enhance quail populations, or to enhance the trail system for better recreation opportunities. Objectives are narrowly focused, concrete, explicit, and usually stated in quantitative terms that can be measured. Examples of objectives are to maximize the rate of return earned on the forest, to double the number of vistas in the forest, to increase the white-tailed deer population by 20%, or to increase recreation areas in the forest from five to ten sites.

- Assessment of the forest condition and history. Planning starts with data gathering. Sometimes existing information is suitable for the development of summary tables, charts, and maps. The history of prior ownership, land use, and forest management activities and planning is important as it explains much of what exists in the forest today. Data on the physical attributes of the forest are a primary need. External factors, like legal and regulatory issues, need to be identified. This process may recognize that the plan will need to address issues like an improperly marked boundary line or an insect infestation. Analysis of the data as part of the planning process often results in the forest owner modifying management objectives due to constraints or opportunities identified in the process.

- Development of plan alternatives. The forest owner is the decision-maker and will decide which alternative best meets his or her management objectives. Of course, the forest owner may want to consider alternatives not presented in the original management plan. For public lands, management plan alternatives may require a process that involves public participation, as the public is the forest owner. Even privately-owned forestland is sometimes subject to public scrutiny, especially large ownerships that might have shareholders.

- Decision by the forest owner on the selected alternative. The owner also sets budgetary limits, revenue expectations, and management limitations. The forester is an agent of the forest owner and is not the decision-maker. All authority is derived from the owner.

- Preparation of the plan documents and implementation of the management plan strategy. This step is where the plan comes together. The formal plan document is prepared as the process continues. The plan usually begins with the forest owner’s management objectives and a resource assessment. Forest stands, maps, charts, tables, and schedules are developed to support the selected alternative. Current conditions are reported, and expected outcomes and cash flows are projected. The result is an operable plan that details the activities that will occur in the forest, including what activities, when they occur, and what is expected to result from the activities (outcomes).

- Evaluation of the results and feedback. Once the plan is developed and implemented, the forest owner will evaluate the results, sometimes directing changes (feedback). The planning process, shown in figure 1, is dynamic and is often modified. 7

Figure 1. General steps involved in a typical forest management planning process. Image credit: Tom Straka, Clemson University.

Silvicultural Considerations

Usually, a forest resource management plan results in a management regime, which is a schedule of silvicultural activities that are expected to take place on the individual forest stands. If a forest stand is expected to produce outcomes consistent with the forest owner’s objectives, decisions must be made on how the silvicultural system and forest management activities will be manipulated to produce the desired outcomes. In terms of silvicultural considerations, these types of decisions involve

- Evaluation of the forest owner’s management objectives and the specific future stand considerations expected. What does the forest owner expect the future forest to look like? What are the outcomes specified in the forest owner’s goals and objectives?

- Which silvicultural systems will best achieve the forest owner’s management objectives? Did the forest owner specify the use or nonuse of certain silvicultural systems? Even-aged, uneven-aged, or group selection silvicultural systems will produce different future stand conditions.

- Does the forest owner favor certain tree species? Should the management plan encourage the regeneration of these tree species? Thinning and regeneration methods within the management regime will impact the future tree species composition in the forest. Shade tolerance, for example, will determine future tree species mix to a degree, and the silviculture practices applied will need to take that into account.

- Vegetation management (herbicides) can be used to release desired tree species and control undesirable tree species and other vegetation. This alternative can be expensive, but under the right conditions, increased forest yield can make the investment attractive.

- Fertilization is a second expensive alternative that can increase forest yield enough in some cases to be an attractive investment.

- Thinning is included in most forest management regimes. Precommercial thinning is a cost to the forest owner but will impact future forest yields and conditions. What does the forest owner expect forest conditions to be? What forest products is the owner trying to grow?

- Some forest owners specify conditions that require special actions. Wildlife management objectives, for example, might require scattered food plots, snag trees, or mast-producing trees. Recreation management objectives might require certain tree species or vistas.

- Site preparation will have a significant impact on the resulting forest stand. Silvicultural practices prior to or during timber harvest will also impact the future forest stand. Site preparation is an expensive option that occurs at the beginning of a timber rotation, so it has a substantial effect on profitability due to the time value of money.

- How is the forest going to be regenerated? Planting controls tree species and density. Natural regeneration requires more skill to obtain desired trees species and density. Cost is a consideration. Planting can be very expensive, but not planting can also be costly if nature does not cooperate to produce desirable future stand conditions. 7

Conclusion

Forest resource management planning is not free, it involves both time and money. A forest owner needs only the amount of planning necessary to achieve his or her goals and objectives. Detail can vary from a mental plan to a precisely written, documented, bound document. Like the forest management objectives, the scale of the management plan is determined by the forest owner’s needs. 8 The forest resource management planning process is an important part of forest ownership that leads to sustainable forest management and happy forest owners with forest outcomes that meet their expectations.

References Cited

- Patterson AE. Technique of forest management plan preparation. Athens (GA): University of Georgia, School of Forestry; 1960.

- Leuschner, WA. Introduction to forest resource management. New York (NY): John Willey & Sons; 1984.

- Straka TJ. Evolution of sustainability in American forest resource planning in the context of the American forest management textbook. Sustainability. 2009 Dec;1(4):838–854.

- Bettinger P, Boston K, Siry JP, Grebner DL. Forest management and planning. Burlington (MA): Academic Press; 2009.

- Straka TJ, Tew RD, Cushing TL. Consanguine philosophies of traditional timber-based and contemporary sustainability-based forest resource management plans. Natural Resources. 2013 Sept;4(5):387–394.

- Thrift TG, Straka TJ, Marsinko AP, Baumann JL. Forest management plans: importance of plan components to nonindustrial private forest landowners in South Carolina. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry. 1997 Nov;21(4):164–167.

- Tew RD, Straka TJ; Cushing TL. The enduring fundamental framework of forest resource management planning. Natural Resources. 2013 Oct; 4(6):423–434.

- Davis LS, Johnson KN. Forest management, 3 rd ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1987.

Publication Adapted from

Tew RD, Straka TJ, Cushing, TL. Forest resource management planning: why plan? The planning process. Clemson (SC): Clemson Extension, Forestry and Natural Resources; 2016; FNR 110. https://sref.info/resources/publications/forest-resource-management-planning-why-plan-the-planning-process.

Author(s)

Puskar Khanal, PhD, Assistant Professor, Forestry and Environmental Conservation Department

Visit Puskar Khanal's Profile

Thomas Straka, PhD, Professor, Forestry and Environmental Conservation Department

Visit Thomas Straka's Profile

Citation

Khanal P, Straka T. Fundamentals of Forest Resource Management Planning. Clemson (SC): Clemson Cooperative Extension, Land-Grant Press by Clemson Extension; 2020 Apr. LGP 1047. http://lgpress.clemson.edu/publication/fundamentals-of-forest-resource-management-planning/.

Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service offers its programs to people of all ages, regardless of race, color, gender, religion, national origin, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or family status and is an equal opportunity employer.

The information in this publication is provided for educational and informational purposes only. The use of any brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by Clemson University nor does it imply discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals may be included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that their intended use of the chemical complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label.

This publication may be reprinted in its entirety for distribution for educational and informational purposes only. Any reference made from this publication must use the provided citation.

![]()