This educational video is a visual version of this article and presented by Artificial Intelligence (AI). Please see our AI ethics and diversity policy for more information on how we use AI and select presenters on our website.

In 1789, France was the powerhouse of Europe, with a large overseas empire, strong colonial trade links as well as a flourishing silk trade at home, and was the centre of the Enlightenment movement in Europe. The Revolution which engulfed France shocked her European counterparts and changed the course of French politics and government completely. Many of its values – liberté, égalité, fraternité – are still widely used as a motto today.

France had an absolute monarchy in the 18th century – life centred around the king, who had complete power. Whilst theoretically this could work well, it was a system heavily dependent on the personality of the king in question. Louis XVI was indecisive, shy and lacked the charisma and charm which his predecessors had so benefited from.

The court at Versailles, just outside Paris, had between 3,000 and 10,000 courtiers living there at any one time, all bound by strict etiquette. Such a large and complex social set required management by the king in order to manage power, bestow favours and keep a watchful eye over potential troublemakers. Louis simply didn’t have the capability or iron will necessary to do this.

Louis’ wife and queen, Marie Antoinette, was an Austrian-born princess whose (supposedly) profligate spending, Austrian sympathies and alleged sexual deviancy were targeted repeatedly. Incapable of acting in a way which might have transformed public opinion, the royal couple saw themselves become scapegoats for far more issues than those which they could control.

‘Marie Antoinette en chemise’, portrait of the queen in a muslin dress (by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1783)

Image Credit: Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As an absolute monarch, Louis was also held somewhat responsible – along with his advisors – for failures. Failures could only be blamed on advisors or external parties for so long, and by the late 1780s, the king himself was the target of popular discontent and anger rather than those around him: a dangerous position for an absolute monarch to be in. Whilst contemporaries may have perceived the king as being anointed by God, it was their subjects who permitted them to maintain this status.

By no means did Louis XVI inherit an easy situation. The power of the French monarchy had peaked under Louis XIV, and by the time Louis XVI inherited, France found herself in an increasingly dire financial situation, weakened by the Seven Years War and American War of Independence.

With an old and inefficient taxation system which saw large portions of the wealthiest parts of French society exempt from major taxes, the burden was carried by the poorest and simply didn’t provide enough cash.

Variations by region also caused unhappiness: Brittany continued to pay the gabelle (salt tax) and the pays d’election no longer had regional autonomy, for example. The system was clunky and unfair, with some areas over-represented and some under-represented in government and through financial contributions. It was desperately in need of sweeping reforms.

The French economy was also growing increasingly stagnant. Hampered by internal tolls and tariffs, regional trade was slow and the agricultural and industrial revolution which was hitting Britain was much slower to arrive, and to be adopted in France.

The Estates System was far from unique to France: this ancient feudal social structure broke society into 3 groups, clergy, nobility and everyone else. In the Medieval period, prior to the boom of the merchant classes, this system did broadly reflect the structure of the world. As more and more prosperous self-made men rose through the ranks, the system’s rigidity became an increasing source of frustration. The new bourgeoise class could only make the leap to the Second Estate (the nobility) through the practice of venality, the buying and selling of offices.

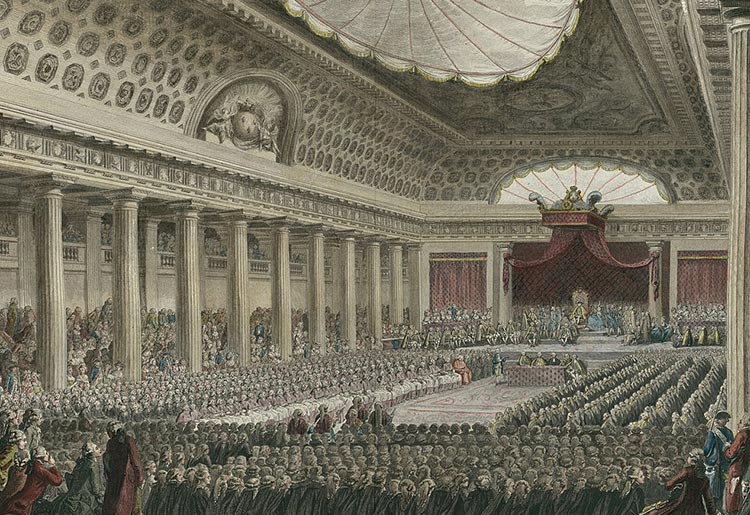

Following parlements blocking of reforms, Louis XVI was persuaded to call an assembly known as the Estates General, which had last been called in 1614. Each estate drew up a list of grievances, the cahier de doleances, which were presented to the king. The event turned into a stalemate, with the First and Second Estates continually voting to block the Third Estate out of a petty desire to keep their status firm, refusing to acknowledge the need to work together to achieve reform.

Opening of the Estates-General in Versailles 5 May 1789

Image Credit: Isidore-Stanislaus Helman (1743-1806) and Charles Monnet (1732-1808), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

These deep divisions between the estates were a major contributing factor to the eruption of revolution. With an ever-growing and increasingly loud Third Estate, the prospect of meaningful societal change began to increasingly appear to be something of a possibility.

French finances were a mess by the late 18th century. The taxation system allowed the wealthiest to avoid paying virtually any tax at all, and given that wealth almost always equalled power, any attempt to push through radical financial reforms was blocked by the parlements. Unable to change the tax, and not daring to increase the burden on those who already shouldered it, Jacques Necker, the finance minister, raised money through taking out loans rather than raising taxes. Whilst this had some short term benefits, loans accrued interest and pushed the country further into debt.

In an attempt to add some form of transparency to royal expenditure and to create a more educated and informed populace, Necker published the Crown’s expenses and accounts in a document known as the Compte rendu au roi. Instead of placating the situation, it in fact gave the people an insight into something they had previously considered to be none of their concern.

With France on the brink of bankruptcy, and people more acutely aware and less tolerant of the feudal financial system they were upholding, the situation was becoming more and more delicate. Attempts to push through radical financial reforms were made, but Louis’ influence was too weak to force his nobles to bend to his will.

Historians debate the influence of Enlightenment in the French Revolution. Individuals like Voltaire and Rousseau espoused values of liberty, equality, tolerance, constitutional government and the separation of church and state. In an age where literacy levels were increasing and printing was cheap, these ideas were discussed and disseminated far more than previous movements had been.

Many also view the philosophy and ideals of the First Republic as being underpinned by Enlightenment ideas, and the motto most closely associated with the revolution itself – ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ – can be seen as a reflection of key ideas in Enlightenment pamphlets.

Voltaire, Portrait by Nicolas de Largillière, c. 1724

Image Credit: Nicolas de Largillière, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Many of these issues were long term factors causing discontent and stagnation in France, but they had not caused revolution to erupt in the first 15 years of Louis’ reign. The real cost of living had increased by 62% between 1741 and 1785, and two successive years of poor harvests in 1788 and 1789 caused the price of bread to be dramatically inflated along with a drop in wages.

This added hardship added an extra layer of resentment and weight to the grievances of the Third Estate, which was largely made up of peasants and a few bourgeoise. Accusations of the extravagant spending of the royal family – irrespective of their truth – further exacerbated tensions, and the king and queen were increasingly targets of libelles and attacks in print.