Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world

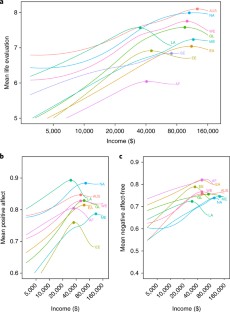

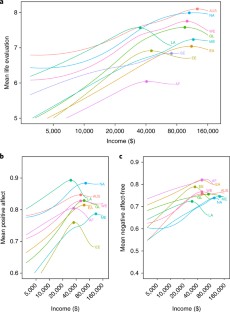

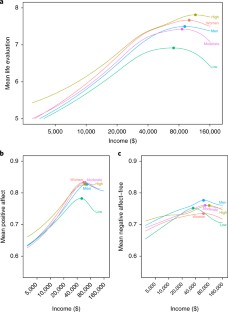

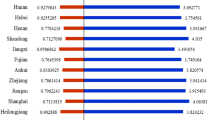

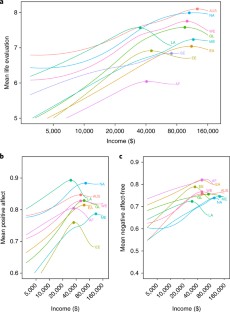

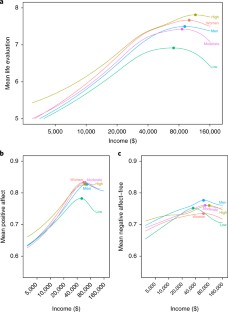

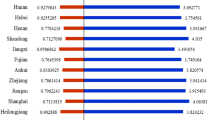

Income is known to be associated with happiness 1 , but debates persist about the exact nature of this relationship 2,3 . Does happiness rise indefinitely with income, or is there a point at which higher incomes no longer lead to greater well-being? We examine this question using data from the Gallup World Poll, a representative sample of over 1.7 million individuals worldwide. Controlling for demographic factors, we use spline regression models to statistically identify points of ‘income satiation’. Globally, we find that satiation occurs at $95,000 for life evaluation and $60,000 to $75,000 for emotional well-being. However, there is substantial variation across world regions, with satiation occurring later in wealthier regions. We also find that in certain parts of the world, incomes beyond satiation are associated with lower life evaluations. These findings on income and happiness have practical and theoretical significance at the individual, institutional and national levels. They point to a degree of happiness adaptation 4,5 and that money influences happiness through the fulfilment of both needs and increasing material desires 6 .

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

133,45 € per year

only 11,12 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Happiness inequality has a Kuznets-style relation with economic growth in China

Article Open access 20 September 2022

Income raises human well-being indefinitely, but age consistently slashes it

Article Open access 11 April 2023

The globalizability of temporal discounting

Article Open access 11 July 2022

References

- Howell, R. T. & Howell, C. J. The relation of economic status to subjective well-being in developing countries: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull.134, 536–560 (2008). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kahneman, D. & Deaton, A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA107, 16489–16493 (2010). ArticleCASPubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Sacks, D. W., Stevenson, B. & Wolfers, J. The new stylized facts about income and subjective well-being. Emotion12, 1181–1187 (2012). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E. & Scollon, C. N. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: revising the adaptation theory of well-being. Am. Psychol.61, 305–314 (2006). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brickman, P. & Campbell, D. T. in Adaptation Level Theory:A Symposium (ed. Appley, M. H.) 287–302 (Academic Press, New York, NY, 1971).

- Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J. & Arora, R. Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.99, 52–61 (2010). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Howell, R. T., Kern, M. L. & Lyubomirsky, S. Health benefits: meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychol. Rev.1, 83–136 (2007). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lucas, R. E. & Schimmack, U. Income and well-being: how big is the gap between the rich and the poor? J. Res. Pers.43, 75–78 (2009). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Diener, E. & Biswas-Diener, R. Will money increase subjective well-being? Soc. Indic. Res.57, 119–169 (2002). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lucas, R. E., Diener, E. E. & Suh, E. Discriminant validity of well-being measures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.71, 616–628 (1996). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stevenson, B. & Wolfers, J. Subjective Well-being and Income: Is There Any Evidence of Satiation? (IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2013); https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2265690

- Gelman, A. The connection between varying treatment effects and the crisis of unreplicable research: a Bayesian perspective. J. Manag.41, 632–643 (2015). Google Scholar

- Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N. & Stone, A. A. Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science312, 1908–1910 (2006). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clark, A. E. Are wages habit-forming? Evidence from micro data. J. Econ. Behav. Organ.39, 179–200 (1999). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Deaton, A. Policy implications of the gradient of health and wealth. Health Aff.21, 13–30 (2002). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Harrell, F. E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis (Springer, New York, NY, 2015).

- Wagenmakers, E.-J. A practical solution to the pervasive problems of P values. Psychon. Bull. Rev.14, 779–804 (2007). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schönbrodt, F. D., Wagenmakers, E., Zehetleitner, M. & Perugini, M. Sequential hypothesis testing with Bayes factors: efficiently testing mean differences. Psychol. Methods22, 322–339 (2017). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- The World Factbook (Central Intelligence Agency, 2009).

- Tay, L., Morrison, M. & Diener, E. Living among the affluent: boon or bane? Psychol. Sci.25, 1235–1241 (2014). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adelmann, P. K. Occupational complexity, control, and personal income: their relation to psychological well-being in men and women. J. Appl. Psychol.72, 529–537 (1987). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Levant, R. & Richmond, K. A review of research on masculinity ideologies using the male role norms inventory. J. Mens. Stud.15, 130–146 (2007). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mahalik, R. et al. Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psychol. Men Masculin.4, 3–25 2003). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stutzer, A. The role of income aspirations in individual happiness. J. Econ. Behav. Organ.54, 89–109 (2004). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Clark, A. E. & Oswald, A. J. Satisfaction and comparison income. J. Public Econ.61, 359–381 (1996). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Clark, A. E. & Senik, C. Who compares to whom? The anatomy of income comparisons in Europe. Econ. J.120, 573–594 (2010). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Diener, E. & Oisho, S. in Culture and Subjective Well-being (eds Diener, E. & Suh, E. M.) 185–218 (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2000).

- Layard, R., Mayraz, G. & Nickell, S. International Differences in Well-Being Ch. 6 (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, NY, 2010).

- Proto, E. & Rustichini, A. A reassessment of the relationship between GDP and life satisfaction. PLoS ONE8, e79358 (2013). ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Kuykendall, L., Tay, L. & Ng, V. Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull.141, 364–403 (2015). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cheung, F. & Lucas, R. E. Income inequality is associated with stronger social comparison effects: the effect of relative income on life satisfaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.110, 332–341 (2016). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. Income and well-being: an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. J. Public Econ.89, 997–1019 (2005). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Divided We Stand – Why Inequality Keeps Rising (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2011).

- Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008)

- Cantril, H. The Pattern of Human Concerns (Rutgers Univ. Press, New Brunswick, 1965).

- Levin, K. A. & Currie, C. Reliability and validity of an adapted version of the Cantril ladder for use with adolescent samples. Soc. Indic. Res.119, 1047–1063 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Palmore, E. & Kivett, V. Changes in life satisfaction: a longitudinal study of persons aged 40–70. J. Gerontol.32, 311–316 (1977). ArticleCASPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beckie, T. M. & Hayduk, L. A. Using perceived health to test the construct-related validity of global quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res.65, 279–298 (2004). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lind, J. T. & Mehlum, H. With or without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat.72, 109–118 (2010). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Korn, E. L. & Graubard, B. I. in Analysis of Health Surveys 345–346 (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 1999).

- Kass, R. E. & Raftery, A. E. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.90, 773–795 (1995). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jeffreys, H. Theory of Probability (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1961).

- Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D. & Iverson, G. Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychon. Bull. Rev.16, 225–237 (2009). ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

Acknowledgements

This research was not supported by any funding.